Conventional herbicides – public perceptions take a dive. Despite the community benefits that herbicides have provided with improved weed control, the perception of conventional herbicides, in the eyes of the public, has taken a few hits.

They have heard via all forms of media that compounds like glyphosate may pose a greater threat to health. There have been many cases being won in favour of various plain-tiffs for large sums of money, suspecting potential links of glyphosate with cancer.

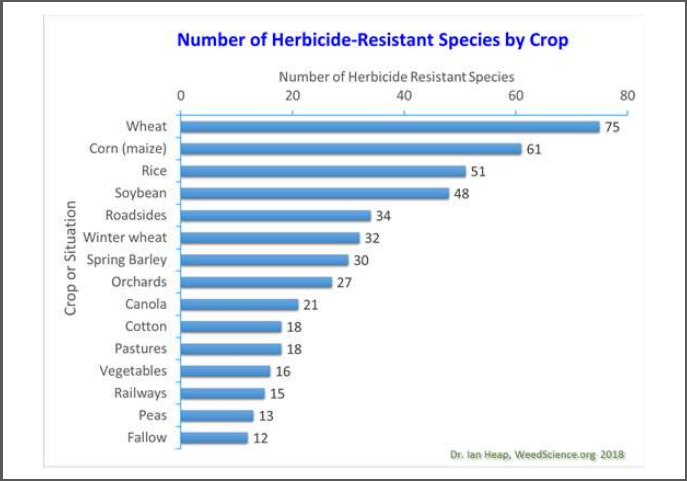

Herbicide resistant weeds are also reducing the value of some products due to poor control. Herbicide resistance, originally found in cropping paddocks with selective herbicides, is now widespread, affecting many situations (road sides, vineyards, non-crop areas etc). Glyphosate resistance in plants is becoming more common, due to its increased use. There has also been steady increases on resistance to other mode-of-action herbicides over the past 20 years. To rub salt into the wounds, reliance on limited herbicide rotations could also result in species shift and/or selection of tolerant species. For example, there have been steady increases in glyphosate toler-ant plants such a Coolatai grass along roadsides, as glyphosate was never 100% effective on this species.

Worldwide trend for herbicide resistance has affected many situations Image: Weedscience.org

Adding to these issues is the general trend in the community for organic, ‘purer’ and safer produce. As such, there is likely to be a greater interest in alternative chemical weed control.

Conventional herbicides – other issues

Off-target damage, such as desirable plant injury or death is a concern. A common example is the physical drift or movement of herbicides; this can then be deposited onto sensitive crops, animals or environments. Classic examples of this are 2,4-D drift onto cotton crops and the movement via water of diuron into the Great Barrier Reef.

Spray drift onto cotton: left untreated and right 2,4-D at 0.1% of standard dose rate Image: Tony Cook

Some of the older herbicides of the 1960’s to 70’s have left a lingering stigma with the public due to serious health effects. Despite the better regulation and testing standards of our federal regulator, the Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority (APVMA), people often remember Agent Orange and other less user-friendly herbicides like arsenic pentoxide. Modern standards have reduced the toxicity of herbicides but really haven’t translated into better perception of modern synthetic herbicides. To make the situation more precarious, a re-cent World Health Organisation review on glyphosate has not improved the profile of conventional herbicides.

The review of many compounds by our regulators could place more restrictions on their use or could result in loss from the market.

About half the synthetic herbicides have some residual activity. Although this can extend weed control, it could be restrictive to planting other crops and infers environmental persistence.

Critique of non-conventional herbicides

A move to alternative herbicides does not necessarily mean a complete step away from all these is-sues. Their introduction as herbicides could have their own list of pros and cons.

But firstly, before we investigate this alternative group of herbicides, let’s get our definitions set. What constitutes the definition of non-conventional herbicides (chemicals)?

Plant based organic herbicides or non-synthetic products.

Chemical exudates from plants or other natural organisms that control weed growth eg. allelopathic crop residues or oils.

The definition does not include synthetically made products, derived from natural compounds like diesel or petrol. Generally, these are not considered a viable option due to OH&S risks because of flammability issues and wear and tear on seals of spray lines. Diesel mixtures, sump oil creosote type brews were used more frequently in the past to mark playing fields – killing weeds effectively. In modern times, they have been substituted for paint-based products that are cheaper and don’t leave a furrow (trip risk) like the old-style petrochemicals.

For this article – biological control of weeds is not included as some may be applied similar to conventional herbicides and may give the impression they are like a chemical treatment (bio-herbicides).

Alternatives to synthetic herbicides include natural chemicals, such as acids, soaps, oils and salts that can act as contact herbicides. These non-synthetic herbicides are best used as a targeted spray or in non-crop areas because contact can lead to damage of plants in production. It is important to note these products do not kill roots and repeated applications will be necessary for weeds that have the ability to regenerate from their roots.

Acid solutions are believed to cause changes in plant cell pH that result in loss of cell membrane integrity and eventual death, via desiccation.

Similarly, salts of fatty acids (soaps) act by penetrating cells and disrupting cell membranes, ultimately causing desiccation and death. Soaps include pelargonic acid, ammonium nonanoate and potassium salts of fatty acids.

Plant-based oils such as cinnamaldehyde (the primary component of cinnamon) have been used as contact herbicides. Oils are believed to cause disruption of cell membranes. Plant-based oils include clove, eugenol, lemongrass, citrus, thyme and oregano.

Salts such as sodium chloride (table salt) or ammonium chloride can be used to kill plants. They cause dehydration of plant tissue via osmosis. Some com-bination products mix acetic acid, salt, citrus oil, eugenol, etc.

Some of the common ingredients that make up the Australian organic herbicide products Image: Tony Cook

There are a number of registered non-conventional products listed on the Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority (APVMA) website. Using this website: https://portal.apvma.gov.au/pubcris and typing in active ingredients like sodium chloride, clove oil, d-limonene, acetic acid, pine oil or nonanoic acid will results in finding a wide range of products.

If one would like to check out the advisory and/or sale-based websites, there are numerous sites that pop up if you type in search words such as natural herbicides or organic herbicides. They do tend to be rather similar, so I found that visiting 5 to 7 sites was enough to give me some variety and differing points of view. Some of these sites are not company based and recommend mixing products that are commonly found around the house. If considering using a natural herbicide, it would be best to use a registered product that has undergone scientific re-view and shown that the label claims on the label are highly likely to work.

Label claims

Most of the products have similar label claims, to control small annual weeds and if larger they are likely to need a repeat spray to control any re-growth (or suppression claims). One product claims to control the viability of seeds. Use patterns are usually for amenity-based areas, concrete paths, industrial areas, some horticultural production activities, non-crop areas and pastures. Other unique use patterns are also catered for depending on the product.

Generally, the list of annual weeds stated are broad-leaf species and very few grass species. This can be best shown by the majority of before and after im-ages showing effective short-term brown-out of broad-leaf species, with reference to Australian based websites. The way these products work, by desiccating the vegetative parts, is by logic not go-ing to kill root systems of perennial plants. For this reason, there is barely any label claims for these weeds. Some may claim suppression or effective short term browning of perennials.

Barnyard grass: decreasing spray rates (salt based herbicide) from left to right. Grasses tend to tolerate desiccant type herbicides better than broad-leaf weeds Image: Tony Cook

Flax-leaf fleabane: increasing weed size at application from left to right. Herbicide used was a salt based product. Sprayed at recommended spray volume. Better control than grasses. Image: Tony Cook

From my brief work with some of these products, I have found them to very fast acting with plants showing symptoms within a few minutes. The best levels of control are seen about 1-3 days after application. They have killed very small glyphosate resistant weeds and appeared to work best on broad-leaf weed species. In summary there could be some niche situations for their use in a broad acre context and could play a role for amenity weed control (edges, non-lawn areas) where public traffic is high. However, if people are accustomed to the ease of use of glyphosate, they need to re-program them-selves to treating more regularly with these alternatives and only when weeds are less than 5 cm high or wide (general rule of thumb).

Flax-leaf fleabane: effect of fast desiccation 1 day after treatment due to salt action. Decreasing spray rates from left to right. Image: Tony Cook

Shifting from conventional herbicides to these alternatives does require some adjustment to expectations with respect to spray application rates. Glyphosate is commonly applied using water boom spray rates between 30 to 150L/ha for broad-acre situations, road sides and other large areas where covering as much ground with limited time is one of the motives. However, these alternative products require very large spray water rates, essentially to drench plants.

This new requirement will make weed control in these areas slower due to spraying time and the need to refill the tank. As such, weed professionals and researchers need to consider novel ways of ap-plying such herbicides to maintain high spray rates whilst covering large areas. There may be some merit to use weed seeking robotic devices to search out light weed infestations and then treat appropriately.

A robotic weeder was developed for the onion industry and has ability to spray weeds Image: Onion world

Spot treating weeds in amenity areas, rights-of-way, pastures and around buildings, for example, will not require much transition to using these new alternatives. Although some effort is still required to target smaller weeds, the spraying technique will only need some slight modification to ensure a more thorough spray coverage. Repeat applications are likely if there are grasses or the weeds are larger than label requirements.

Story and photos courtesy of Tony Cook – Technical Specialist Weeds | Weeds Research Unit | Invasive Species – Biosecurity – NSW Department of Primary Industries