According to Benbrook (1), primary producers applied about 51.3 million kilograms of glyphosate worldwide in 1995.

However, the quantities of glyphosate used globally have increased rapidly with the ever-increasing adoption of Genetically Engineered – Herbicide Tolerant (GE-HT) crops, especially in the USA.

In 2014, global arable cropping land totaled about 1.4 billion hectares, with an estimated 747 million kilograms of glyphosate applied. So, this area and volume used equates to a potential average of about 0.53 kilogram of glyphosate per hectare, sprayed across all cropping land globally, what an incredible statistic.

Glyphosate, out of patent, now represents a low cost, broad spectrum weed killer that translocates through to the distal roots from a foliar application. It is less toxic than salt on an acute oral LD50 basis.

Given average rates of pesticides used in practice range from 1.5–2.0 kilogram/hectare, the total volume of glyphosate active applied in 2014 would have been sufficient to treat up to 30% of available cropped land that year.

No other pesticide comes even close to this sort of global success, but given every action has an equal and opposite reaction, are we considering the risks attached to the benefits of such global adoption of herbicidal weed control with the same mode of action? Just as medicines have side effects which may affect 0.1 to 1% of the population with an uncommon side effect classification, then it would be prudent to consider the cost to benefit analysis of such widespread glyphosate adoption worldwide.

Use of Glyphosate

Few would argue the benefits broad spectrum weed control of fallow land using glyphosate at a low cost (including fuel savings) has brought croppers. This is in terms of preserving both soil moisture and plant available nitrogen and improving gross margins, in fact for every $1 spent on herbicides there can be up to an 8-fold return on investment (See weedsmart.org ). In a dry continent like Australia it is thought that up to 1/2 of the topsoil of cultivated land has been lost in the last century or so due to erosion. Reference (2) puts yearly soil losses to erosion in Australia at between 5 and 10 tons/hectare/year, hence the widespread adoption of “No or Zero Till” using herbicides like glyphosate to try and mitigate these erosion losses.

One can’t ignore the benefits to amenity areas as well in terms of low cost weed control maintaining the aesthetics and functionality of public parks, ovals and amenity areas, private gardens, bushland, aquatic areas as well as roadsides. There is no doubt that to remove or diminish the use of glyphosate for weed control in Australia would significantly increase the cost of weed control. Just think of the difference between the costs of spraying aquatic weeds with aquatic use approved glyphosates versus using a mechanical harvester.

The Costs/Risks

Is There a Risk to Human Health?

- In March 2015, the World Health Organization’s (WHO) International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) classified glyphosate as “probably carcinogenic in humans” (category 2A) based on their investigative studies.

- In November 2015, the EFSA published an updated assessment report on glyphosate, concluding that “the substance is unlikely to be genotoxic or pose a carcinogenic threat to humans”.

- In May 2016, the Joint Food Agriculture Organization (FAO)/ World Health Organization (WHO) Meeting on Pesticide Residues (JMPR) concluded that “glyphosate is unlikely to pose a carcinogenic risk to humans from exposure through the diet”, even at doses as high as 2,000 milligram/kilogram body weight orally.

- In September 2016, a systematic review found no support for a causal relationship between glyphosate exposure and the risk of non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma (NHL) or of multiple myeloma (3).

So, in terms of chronic effects on human health, you would be better to focus on the risks of known carcinogens such as diesel exhaust, nicotine and the ethanol/acetaldehyde in alcoholic beverages than concern yourself with glyphosate, see IARC monographs.

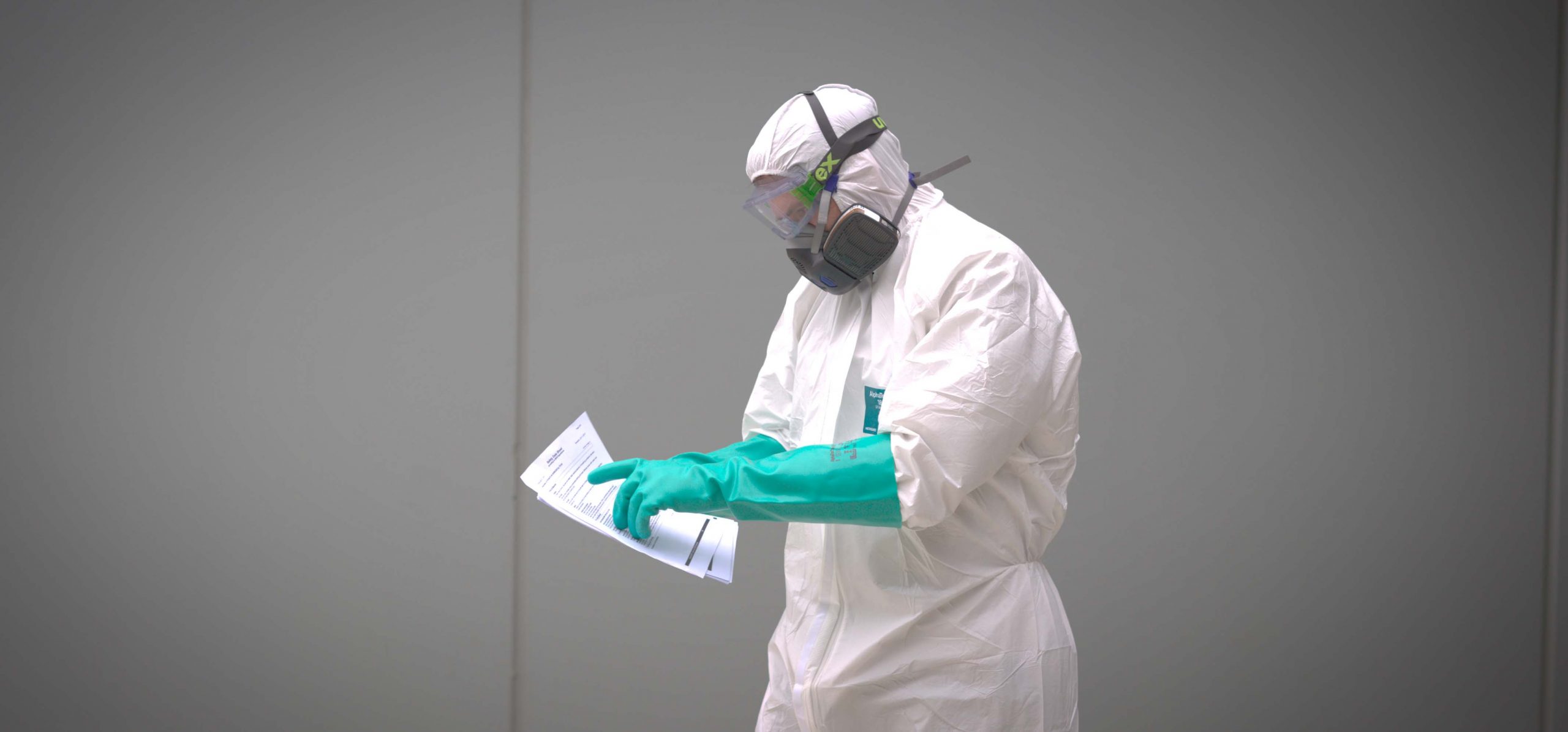

However, users should always follow label safety directions and show particular care when handling the concentrate as the exposures risks when mixing/loading pesticides are 10 to 20 times greater than when it is diluted and applied, according to Syngenta.

The other consideration is the toxicity of the surfactant, and studies have shown the acute oral LD50 (rats) of polyoxyethyleneamine (POEA), the tallow amine surfactant in the early Roundup formulations, is less than a 1/3 of glyphosate itself (4). Hence the development of the aquatic approved glyphosate formulations, which utilize the alkyl betaine surfactant and deliver lower toxicity both to humans (less eye irritation) and aquatic life.

Soil Health

There has been considerable talk but limited scientific research about the potential negative effects of glyphosate use on soil biota, which are all organisms in the soil including earthworms, nematodes, protozoa, fungi and bacteria, not forgetting invertebrates from the phylum arthropoda (insects, spiders etc.).

In a summary of literature (5) on the matter it is stated, “Numerous studies have found that glyphosate applied at standard application rates (PEC = 3 milligram /kilogram), has little impact on the microbial biomass in soil, and stimulation rather than inhibition is more commonly observed. In some cases, glyphosate has a variable effect over time, with increases, decreases, or no effects being observed periodically after the initial exposure”. Note that the PEC is the predicted concentration in the top 50 milligrams of soil based on a 2.2 kilogram/hectare label application rate. In terms of longer term effects, reference (5) goes on to state “To date, there is little evidence to suggest that long-term, repeat applications of glyphosate to soil causes negative shifts in soil microbial communities or functions”.

Anyways check out this exhaustive literature review for yourself to help form a balanced opinion.

Weed Resistance

Glyphosate is becoming a victim of its own success concerning weed resistance. If you go to the Croplife Australian website, and to look at their Herbicide Resistant Weeds section, there are many sites around Australia with resistance confirmed to Group M Herbicide (i.e. glyphosate actives) by weeds such as Annual ryegrass, Awnless barnyard grass, Windmill grass and Common sowthistle to name a few key ones.

For guidance on how to preserve glyphosate’s efficacy on susceptible weed species, search out the Integrated Weed Manual from the Grains Research and Development Corporation (GRDC) website.

Summary

In summary, the risk level to humans of chronic health issues, such as cancer, from repeated exposure to glyphosate has been downgraded to unlikely by the Joint FAO/WHO Meeting on Pesticide Residues (JMPR) body.

Furthermore, with the selection pressures that 40 years of repeated glyphosate use has placed on the weedscape in Australia, it is probable that the quantity used has reached a plateau and will decline going forward, meaning less exposure and risk.

If you are concerned with the health and environmental ramifications of using this versatile herbicide, use the formulations approved for use in aquatic weed control, in tandem with other modes of action and non-chemical techniques. Where a mixture is used, wear all the Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) specified on the higher-level safety directions.

It is hard to imagine future weed control without glyphosate as a significantly used tool in the weed control toolbox. No system is perfect nor without some hazardous aspect, but all in all, glyphosate has served us well in the last 40 years.

References

- Benbrook, C. (n.d.). Trends in glyphosate herbicide use in the United States and globally. [online] Springer Open. Available at: https://enveurope.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s12302-016-0070-0 [Accessed 8 Sep. 2017].

- http://people.oregonstate.edu/~muirp/erosion.htm

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Glyphosate

- https://www.fs.fed.us/foresthealth/pesticide/pdfs/Surfactants.pdf

- Rose, M., Cavagnaro, T., Scanlan, C., Rose, T., Vancov, T., Kimber, S., Kennedy, I., Kookana, R. and Van Zwieten, L. (2016). Impact of Herbicides on Soil Biology and Function. [online] ScienceDirect. Available at: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0065211315001492?via%3Dihub [Accessed 20 Sep. 2017].