Glyphosate is the world’s most widely used herbicide with approximately 8.6 billion kg used worldwide between 1974 and 2014. This works out to approximately 0.53 kg being used on every cropping hectare each year.

Glyphosate resistant crops account for 56% of all glyphosate used (Benbrook 2016). Glyphosate could be said to be the lynch pin of our current farming system. It is therefore of some concern that recently the Californian Superior Court awarded $AU390 million to a school groundskeeper dying of cancer allegedly through the use of glyphosate. Add to this the fact that Monsanto faces more than 5,000 similar lawsuits across the United States over a range of glyphosate-related claims.

Further south, a Brazilian court recommended the Brazilian health regulation agency (ANVISA) conduct a toxicological review of glyphosate. The court suspended the registration of glyphosate in Brazil until the herbicide has been reviewed. Brazil will be the world’s largest soybean producer in 2018-19 and over 85% of its soybeans are Roundup Ready.

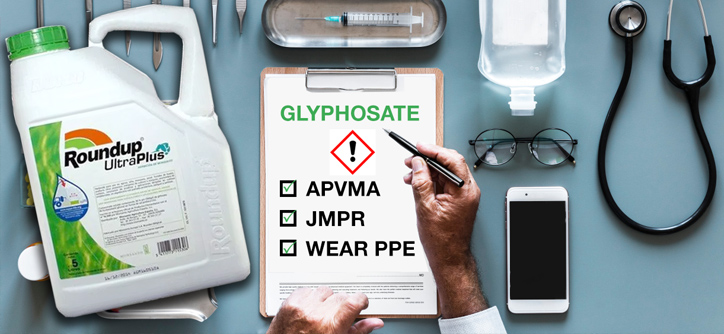

These court cases have also stoked consumer concern about food safety. While the use of glyphosate is not currently under threat in Australia, the Californian and Brazilian court cases mean Australia’s herbicide stewardship must remain world’s best practice.

A range of glyphosate based products can be purchased in your local supermarket.

A range of glyphosate based products can be purchased in your local supermarket.

The outcomes of these two court cases are based on the 2015 International Agency for research on Cancer (IARC) assessment of glyphosate which said that glyphosate is a potential human carcinogen. The IARC looked at the hazard of glyphosate as a cancer-causing agent however it did not consider how the risks are managed when glyphosate is used according to label directions.

The IARC report also found these are also potential human carcinogens:

- indoor emissions from burning wood

- high temperature frying

- some types of shiftwork

- consumption of red meat

Other agents rated as carcinogenic to humans by IARC include:

- alcoholic beverages

- eating processed meat e.g. salami, ham

- sunlight

- post-menopausal hormone therapy

- outdoor air pollution

- the occupation of house painter

- soot, wood dust

The APVMA supports the use of glyphosate in Australia and it can be used safely according to label directions. Following the 2015 IARC report the APVMA conducted its own glyphosate risk assessment and found there was no reason to place it under formal reconsideration.

A number of other regulators around the world have also conducted assessments of glyphosate. These include:

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) 2018 – using a risk-based weight of evidence found glyphosate did not cause cancer in humans

- New Zealand Environmental Protection Agency – found in 2016 that glyphosate was unlikely to cause cancer

- US Environmental Protection Agency – found in 2016 that glyphosate was unlikely to cause cancer in humans

- Health Canada’s Pest Management Regulatory Agency – found in 2015 that glyphosate was unlikely to cause cancer

In the largest study of its kind; the US National Cancer Institute conducted the Agricultural health study in Iowa and North Carolina which studied 89,000 farmers and spouses dating back to 1993. Glyphosate was used on 83% of the participant’s farms. The study found no association with solid tumours or lymphoid malignancies including non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (the cancer of the Californian groundsman awarded damages recently).

What has added to the general public’s concern about glyphosate is California’s Safe drinking water and toxic enforcement act 1986 (Proposition 65) which publishes a list of chemicals known to cause cancer and based on the 2015 IARC report included glyphosate.

Consumer trust

Consumer trust is being tested with multiple stories in the media about these court cases. Many stories are confrontational, often with very little accurate science presented. In fact the general public’s trust in science is seriously under attack by a range of pseudo-scientists out to sell books on their latest theories and ways to stay healthy. The majority of urban residents have little knowledge of where their food comes from or how it is produced. Most consumers have not been trained to analyse information and actually question where stories and information come from.

As an example a group in the US called the Environmental Working Group (EWG) have the motto “Know your environment. Protect your health.” The website is very slick with lots of photos of healthy vibrant people and reviews of a range of topics that affect consumers. Related to the theme of this article is a page under EWG’s Children’s Health Initiative with the heading “Breakfast with a dose of Roundup? – Weed killer in $289 million cancer verdict found in oats cereal and granola bars.” If that doesn’t get your attention nothing will. The article is well written with a bit of science and quite a bit of emotive language. EWG had sent a range of oat-based breakfast products to a laboratory to be tested for glyphosate residues. Out of the 45 samples from ‘conventional’ agriculture; glyphosate was detected in 43, with 31 samples being above their 0.16 mg/kg stated health benchmark. Note that in Australia glyphosate is not registered in oats for pre-harvest application, but is in North America.

A problem with these stories is that you have to do a lot of digging to get down to the facts.

It is interesting that this same group looked at sugar in children’s breakfast cereals and concluded that a child eating a bowl a day would consume 4.6 kg of sugar over 12 months. Which story would worry you most as a parent?

Australia must maintain good stewardship

While Australia would have the best pesticide regulatory system in the world this is no time for complacency. We must use world’s best stewardship practice with all pesticides. It is essential that advisers and growers follow labels and permits closely as many all our trading partners are often looking for non-tariff barriers to trade. For example China has no maximum residue limit level set for many grains they import so can immediately set an allowable Maximum Residue Limit (MRL) if they want to reduce imports or negotiate on price.

Australian grain industry body Grain Trade Australia has strict codes of practice which growers and advisers should carefully follow.

Most grain buyers are also bringing in stricter monitoring of grain quality and can trace back to individual loads. New technology also allows the testing of samples at the grain receivals point. The importance of this issue is reflected in Co-operative Bulk Handling (CBH Group) in Western Australia introducing a 3-strikes policy regarding the delivery of contaminated grain as a warning that they are serious about grain quality.

Glyphosate is registered for use as a pre-harvest emergent herbicide on wheat, canola, chickpeas, lentils, field peas and faba beans, and has an emergency permit (Permit PER82594) for use on feed and food barley, but not malt barley.

Pre harvest spraying can help reduce weed seed set and enable even ripening of the crop. However application of pesticides close to harvest increases the risk of unacceptable levels of residues being detected in grain.

Top row of barley at 27% -the correct time for glyphosate while the bottom row are 34%, which is too early. Image: Craig Brown

Top row of barley at 27% -the correct time for glyphosate while the bottom row are 34%, which is too early. Image: Craig Brown

A management problem with applying pesticides at this time is the grower determining whether the crop is at the right stage. For example when glyphosate is applied to barley, the maximum moisture content is 27% (late dough), with a minimum 5 day harvest withholding. Determining 27% moisture takes a bit of effort and the crop can be greener than you would think as shown in image 2. Subsequently applications are then often delayed due to a miscalculation of the acceptable stage or spraying logistics which in turn increases the risk of unacceptable grain residues. On the other hand applying glyphosate too early can affect grain quality and yield.

Therefore it is my personal opinion that the late use of glyphosate in crops should be reviewed and alternative weed management strategies be investigated and promoted.

Andrew Storrie, AGRONOMO